Cancer.gov

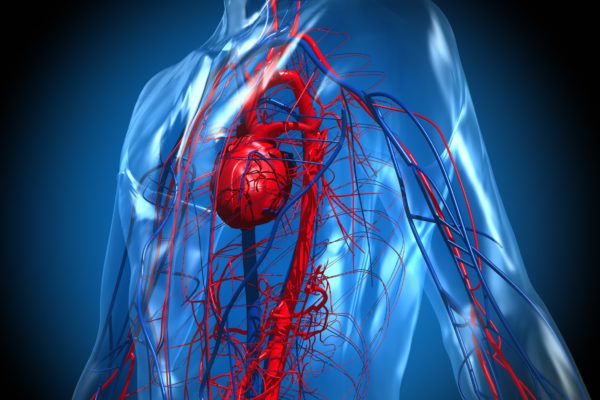

Thymus cancers are rare. The thymus is a small organ located just behind the breast bone (sternum) in the front part of the chest. The thymus is situated in the mediastinum: the space in the chest between the lungs that also contains the heart, part of the aorta, the oesophagus, part of the trachea (windpipe) and many lymph nodes. The thymus sits just in front of and above the heart.

The thymus is divided into two halves, called lobes. It has an irregular shape, and a lot of small bumps, called lobules, are situated on its surface. The thymus has three main layers: the medulla is the inside part of the thymus; the cortex is the layer that surrounds the medulla; and the capsule is the thin covering over the outside of the thymus.

The thymus reaches its maximum weight of about 1 ounce during puberty. It then decreases in size during adulthood, as it's replaced by fat tissue. The thymus is an important part of the body’s immune system. During foetal development and childhood, the thymus is involved in the production and maturation of T lymphocytes (also known as T cells), a type of white blood cell. T lymphocytes develop in the thymus and then travel to lymph nodes (bean-sized collections of immune system cells) throughout the body. There they help the immune system protect the body from viruses, fungus and other types of infections.

The thymus is made of different cell types. Each kind can develop into different cancer types. Three main types of thymus cancer are distinguished.

Thymus cancer is rare. In Belgium, 49 cases were diagnosed in 2015, on over 67,000 new cancer cases. Thymus cancer comes with a relatively good outlook: 85% of patients are still alive one year after diagnosis, and 65% are alive at 5 years.

Tumours in the thymus are usually discovered by accident. In early stages of their development, thymus tumours don’t cause any noticeable symptoms. When symptoms do occur, they can vary from patient to patient. These include:

Around 30% of thymoma patients will also develop myasthenia gravis. This is an auto-immune disease that hampers communication between nerves and muscles. This usually concentrates around the eyes: patients experience difficulty with controlling their eyelids and eye muscles, which can lead to double vision and fatigue.

No known cause for thymus cancer has been identified so far. There are also no known risk factors that increase the chance of contracting thymus cancer.

Given the diversity of symptoms and the relative rarity of the cancer, a GP may not immediately suspect a cancer of the thymus, but when symptoms persist, the patient will most likely be referred to a lung specialist or neurologist at the hospital for further testing. These tests may include: a lung X-ray, CT scan, MRI scan, PET-CT scan or a biopsy.

When the diagnosis of thymus cancer has been established, the exact stage of development will be determined. This will be the basis of predicting the outlook and choosing a treatment strategy. Thymus cancer is classified along the TNM grading system. The T stands for the primary tumour and whether it has spread or not; the N determines whether spreading into the lymph nodes has occurred; and M denotes spreading to organs and tissue elsewhere in the body.

Another key point in grading the tumour is determining the cells that make up the tumour. The ratio between epithelial cells and lymphocytes is important to determine the outlook and the treatment strategy.

When a diagnosis of thymus cancer has been established, a team of specialists will decide on a treatment plan, based on the location and advancement of the cancer. For people with thymus cancer, surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy are on offer. If surgery is an option, the surgeon can opt to take out the entire thymus, or just a part of it. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy can be offered before surgery, in order to shrink the tumour, or after surgery to lower the possibility of the disease coming back or to get rid of cancerous residue. Both treatments are also offered as part of a palliative strategy, when healing is no longer an option. Furthermore, the use of mTOR and RTK inhibitors are currently under investigation in this cancer setting.